The movements of working children in Bolivia have recently made international news for their productive meeting with President Evo Morales, after which he made an official statement that “child labor should not be banned.” Responding to a legislative proposal to ban all children under the age of fourteen from any kind of work, Morales drew on his own experience as a working child and on his conversation with representatives from the Bolivian working children’s movements to not only argue that banning child labor can make it more dangerous (as it goes underground) but also that working children are often working to support their families or to fund their own education, and thus demonstrate a “social conscience.” Echoing some of the language of the movement, Morales also clearly stated that child laborers should not be exploited, and that they deserve and need the protection of the state. Morales’ agreement with the NATs on the potential value and importance of their work is remarkable in the context of the hegemonic international narratives about the need to abolish all child labor and the ongoing pressure on developing nations to raise their minimum age laws. It is a statement that positions him in opposition to some powerful social and political forces and is being seen by working children’s movements around Latin America as a major success. Notes of congratulations and solidarity have been sent from the Latin American transnational movement and from several different national organizations of working kids. The meeting last week was the result of many years of organization, education, and advocacy, and came only after public indignation over violent police repression of a march of working children. It reminds us that children’s movements are not merely spaces of learning, but also can be highly effective at achieving their political goals. It also provides an opportunity to consider some of the tensions within public discourses on working children. The image of working children as pure victims — as tragic innocents exploited by unscrupulous adults — is hard to reconcile with the pictures of these same children sitting with the President, smiling, and telling him that they want to be able to keep their jobs. Working children’s voices and their stories about why they like their work and why they want to work substantially call into question the association of “child labor” only with its worst and most brutal forms. New calls for listening to children and for children’s “participation” in public life all suggest that children’s perspectives should be heard. But, the perspectives of working children challenge many of the common assumptions about child labor, making these voices hard to integrate into the hegemonic and “common-sense” public narratives. Thus, many of the news stories on this important meeting seem a bit confused, presenting a whole array of ILO statistics on child labor alongside the various statements of Morales and the NATs without attempting to figure out how these different elements actually relate to another.

Jessica K. Taft

Sociological fragments on kids, politics, and social change

Tag: Working Children

Starting tomorrow, the International Labor Organization will be hosting a Global Conference on Child Labor in Brasilia. In response to this conference, the Latin American and Caribbean movement of working children has made the statement that I post below. As a scholar of social movements, the thing I find most striking about this statement is the fact that it is just the most recent in a long chain of very similar statements written by the movement over the past 20 years. The movement appears, from my perspective, to be somewhat stuck in the same “tactical repertoire” and has not yet found an effective way to challenge and engage with the major global institution that is one of its primary targets/opponents. Questions of long-term movement strategy and whether and how to make tactical shifts are, perhaps, hard to address in the context of a movement where participants “age out” of leadership so quickly? In any case, the critiques offered by the movement in this statement, and in many others, are quite important, but their impact continues to be limited.

I post the full statement here in order to share more of how the movement of working children approaches the subject of “child labor” and their rejection of the ILO’s goal of its eradication. [Note: the translation is my own].

MOLACNATs Statement: A Response to the Third Global Conference on Child Labor, Brasilia 2013

We, the organized working children and adolescents of Latin America, based on our more than 30 years of experience at the local, national, and regional levels, want to express our opinion publicly in response to the new event promoted by the ILO, The Third Global Conference on Child Labor, which will occur from the 8th-11th of October in Brasilia, Brazil. Our statement here draws on many years of lived experience, and on our own diverse realities, particularly on our experiences working in Latin America. Various cultural, social and economic factors shape and determine our work experiences and the ways that we, and our families, understand the role of work in our lives.

Our analysis and opinion presented here focuses on the preparatory documents for the event in Brazil: “Base Document of the 3rd Global Conference on Child Labor” and “Marking Progress Against Child Labor.”

- Despite the fact that they speak of open, democratic participation in the processes of preparation and consultation for these documents and for the event in Brazil, once more organized working children, who have direct experience with the topic of “child labor,” have been excluded. In addition to being a violation of the principle of participation, expressed in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, our absence from these spaces of discussion and of the creation of policies, disallows the inclusion of alternative perspectives on what the ILO has acknowledged to be a complex and multi-faceted issue.

- These preparatory documents claim that the Convention on the Rights of the Child states that child labor is “a violation of the human rights of the child.” However, article 32 states explicitly children’s right to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous, to interfere with his or her education, or to be harmful to the child’s health, or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development. The language of the Convention clearly establishes that what needs to be combatted is economic exploitation in work, not work itself.

- As with the event at The Hague in 2010, these documents use statistics on the quantity of working children at a global level that, from our perspective, do not correspond with reality. This is an important element to take into account when claims are being made regarding the supposed effectiveness of the policies that have been implemented under the logic of the gradual elimination of child labor. There are discrepancies amongst the various documents published from within the United Nations and the research studies conducted in individual countries, some of which have indicated that either the number of working children in the world has increased or that the decrease has been very small or non-existent. In this sense, and in response to the campaign launched in 2010 with the “Road Map” for abolishing the worst forms of child labor by 2016, we would argue that the results are not as positive as the preparatory documents suggest.

- The ILO continues to base their reports on an assumed mechanical relationship between school desertion and children’s work and/or the educational deficiencies of children who work and study at the same time. This is despite the fact that the presented statistics show that 70% of children who work also go to school, and other research has demonstrated that in many cases work is what enables us to continue to study, and that the experience of work also can be educational for us in many ways.

- Our attention is also drawn to how the ILO addresses domestic work. On the one hand, domestic work is only included in their statistics when it is done in the homes of other people. On the other hand, when they make reference to the work that we do in our own homes, or with and for our own families, it is not included in the statistics and is often presented in a negative way. There is no consideration of how these practices are related to our cultures, or how they have positive elements like supporting our education or the construction of solidarity in our families. Furthermore, the statistics in this case are especially arbitrary and do not provide a global estimate of the labor done in our own homes, which would certainly considerably increase the number of children and adolescents who work.

- We note that the ILO and those who are part of its international advocacy do not assume nor assign any responsibility for the crisis in the global economic system, nor for the consequences that the crisis has generated for the majority of the global population, whether they be adult, youth, and child workers. The Brasilia Base Document only states in an abstract and general way that, “the structure of the labor market… does influence the incidence of child labor in different ways. Firstly, the existence of an informal economy means that often a significant part of the economic and labor relationships escapes regulation and inspection by competent authorities, opening the way for the use and exploitation of the work force of children.”

- The documents reflect a stigmatization of cultural patterns that, according to the studies, are determinants that increase the occurrence of child labor. This stigmatization and criticism of our cultures is used to explain and justify the failures of policies that not worked to eradicate child labor, such as cash transfer programs.

Finally, we would like to express to the society at large, that, as a social movement, we are committed to continuing to struggle to achieve the implementation of the rights of children and adolescents, in general, and working children and adolescents in particular, and to working together with other popular sectors for the creation of policies that can transform our world.

MOLACNATS, September 30, 2013

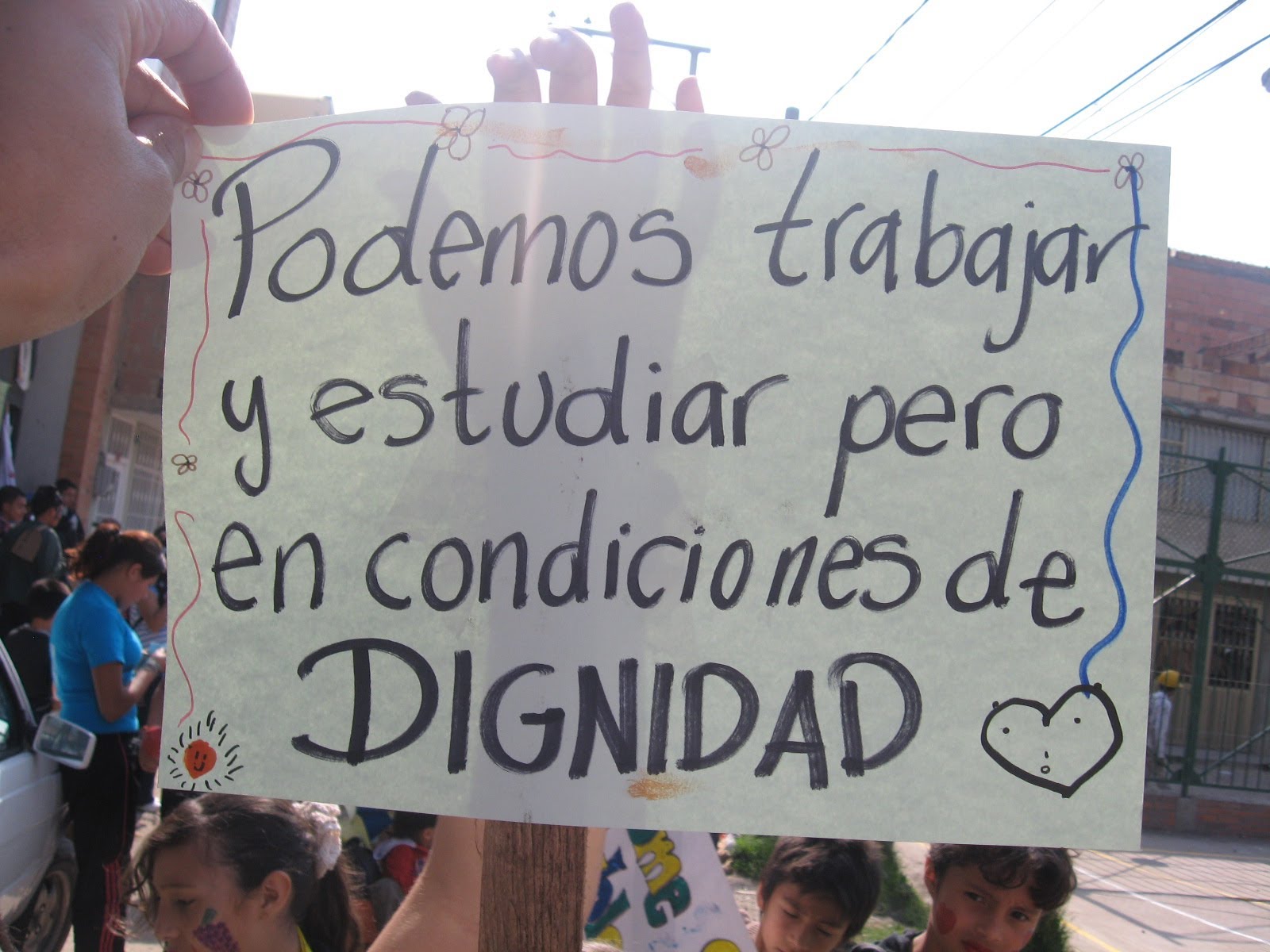

One of the key concepts in the movement of working children here in Peru is the idea of “trabajo digno.” The movement argues that kids should be able to work, but, like everyone else, deserve to work in jobs that are fair, safe, and non-exploitative. As this sign indicates, they argue that kids should be able to work and to go to school, and that both spaces should be spaces that respect their rights, that offer them dignity as full persons.

This concept of “trabajo digno” is often translated into English as “decent work.” But as I think more about what kids and adults here mean by the term, I am less and less pleased with this translation. Work that is decent seems like a great deal less than what is being imagined by this movement. Decent work may draw our attention to pay, occupational safety, and hours worked, but I’m not sure it captures the less material dimensions of what makes for a good job, or fair and just working conditions. Furthermore, when talking about trabajo digno, people in the movement here also talk about it as respecting and fostering the humanity of the worker. At times, this resonates with more explicitly Marxist theories around alienated labor and work as central to what it means to be human. Trabajo digno, at least as it is sometimes used by participants in the movement of working children, is far more than just “decent work” — it is non-alienated labor. And the quest for it is therefore far more radical and expansive than it would first appear in these English translations.

So, does anyone out there have examples of other ways this has been translated? Are scholars who study labor movements across the Americas using a different translation?

© 2025 Jessica K. Taft

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑