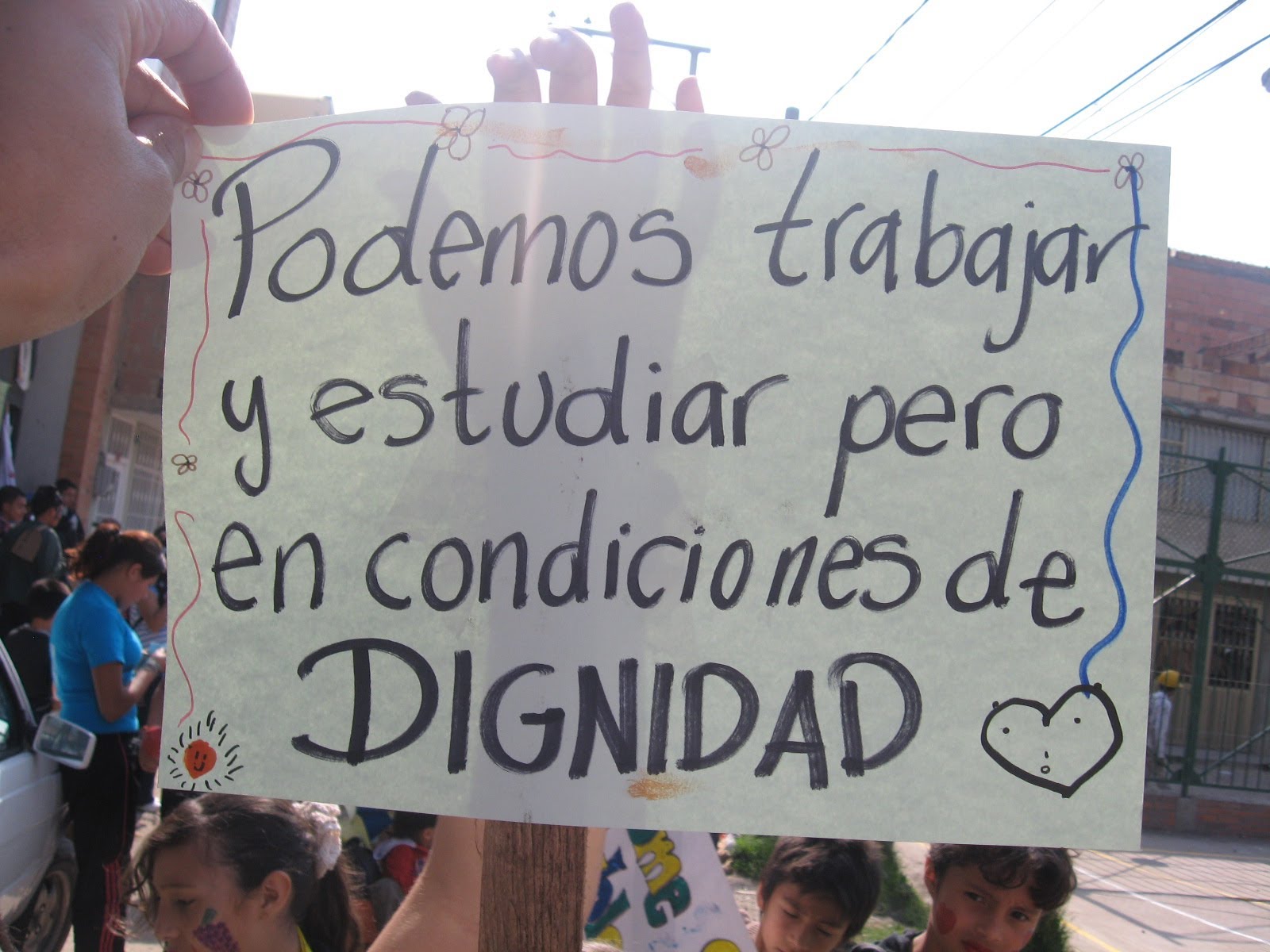

One of the key concepts in the movement of working children here in Peru is the idea of “trabajo digno.” The movement argues that kids should be able to work, but, like everyone else, deserve to work in jobs that are fair, safe, and non-exploitative. As this sign indicates, they argue that kids should be able to work and to go to school, and that both spaces should be spaces that respect their rights, that offer them dignity as full persons.

This concept of “trabajo digno” is often translated into English as “decent work.” But as I think more about what kids and adults here mean by the term, I am less and less pleased with this translation. Work that is decent seems like a great deal less than what is being imagined by this movement. Decent work may draw our attention to pay, occupational safety, and hours worked, but I’m not sure it captures the less material dimensions of what makes for a good job, or fair and just working conditions. Furthermore, when talking about trabajo digno, people in the movement here also talk about it as respecting and fostering the humanity of the worker. At times, this resonates with more explicitly Marxist theories around alienated labor and work as central to what it means to be human. Trabajo digno, at least as it is sometimes used by participants in the movement of working children, is far more than just “decent work” — it is non-alienated labor. And the quest for it is therefore far more radical and expansive than it would first appear in these English translations.

So, does anyone out there have examples of other ways this has been translated? Are scholars who study labor movements across the Americas using a different translation?

Leave a Reply